Ariel: The Youngest of Uranus's Major Moons

Ariel is the fourth-largest of Uranus's five major moons and has the youngest, most geologically active surface of the group. The moon is crisscrossed by extensive fault systems and canyons, evidence of past tectonic activity that may have been driven by tidal heating or other processes. Ariel's surface shows a mix of heavily cratered ancient terrain and smooth, young regions that have been resurfaced, suggesting the moon was once more geologically active. The extensive fault systems, some hundreds of kilometers long, indicate significant crustal extension. Ariel is brighter than Umbriel, its darker sibling, and shows evidence of past cryovolcanism or other resurfacing processes. This article explores Ariel's extensive fault systems, past geological activity, composition, and its place among Uranus's moons.

In Simple Terms

Imagine a moon that looks like it's been cracked and stretched like a piece of taffy—that's Ariel, one of Uranus's moons. It's covered in giant canyons and cracks that stretch for hundreds of kilometers, some so deep they would make Earth's Grand Canyon look small. What makes Ariel special is that it's the brightest and most geologically active of Uranus's major moons, with a surface that shows clear signs of past activity. Some parts of Ariel are covered in ancient craters from billions of years ago, while other parts are smooth and young, like the surface was recently resurfaced with fresh ice. Scientists think Ariel might have been heated up in the past, possibly from Uranus's gravity pulling and stretching it, which could have caused the moon's surface to crack and split. Even though Ariel is quiet now, its surface tells the story of a moon that was once much more active, with ice volcanoes and tectonic forces reshaping its surface. It's like looking at a frozen snapshot of geological activity from millions of years ago.

Abstract

Ariel is the fourth-largest of Uranus's five major moons, with a radius of 579 km and a mass of 1.35 × 10²¹ kg. The moon orbits Uranus at 191,020 km, completing an orbit in 2.52 days. Ariel has the youngest, most geologically active surface of Uranus's major moons, with extensive fault systems and canyons crisscrossing its surface. The faults, some hundreds of kilometers long, indicate significant crustal extension and past tectonic activity. Ariel's surface shows a mix of heavily cratered ancient terrain and smooth, young regions that have been resurfaced, suggesting the moon was once more geologically active, possibly driven by tidal heating or other processes. The moon is brighter than Umbriel, its darker sibling, with an albedo of 0.53 compared to Umbriel's 0.19. Ariel shows evidence of past cryovolcanism or other resurfacing processes that covered older craters. The moon is composed primarily of water ice with a small amount of rock. This article reviews Ariel's extensive fault systems, past geological activity, composition, and exploration by Voyager 2.

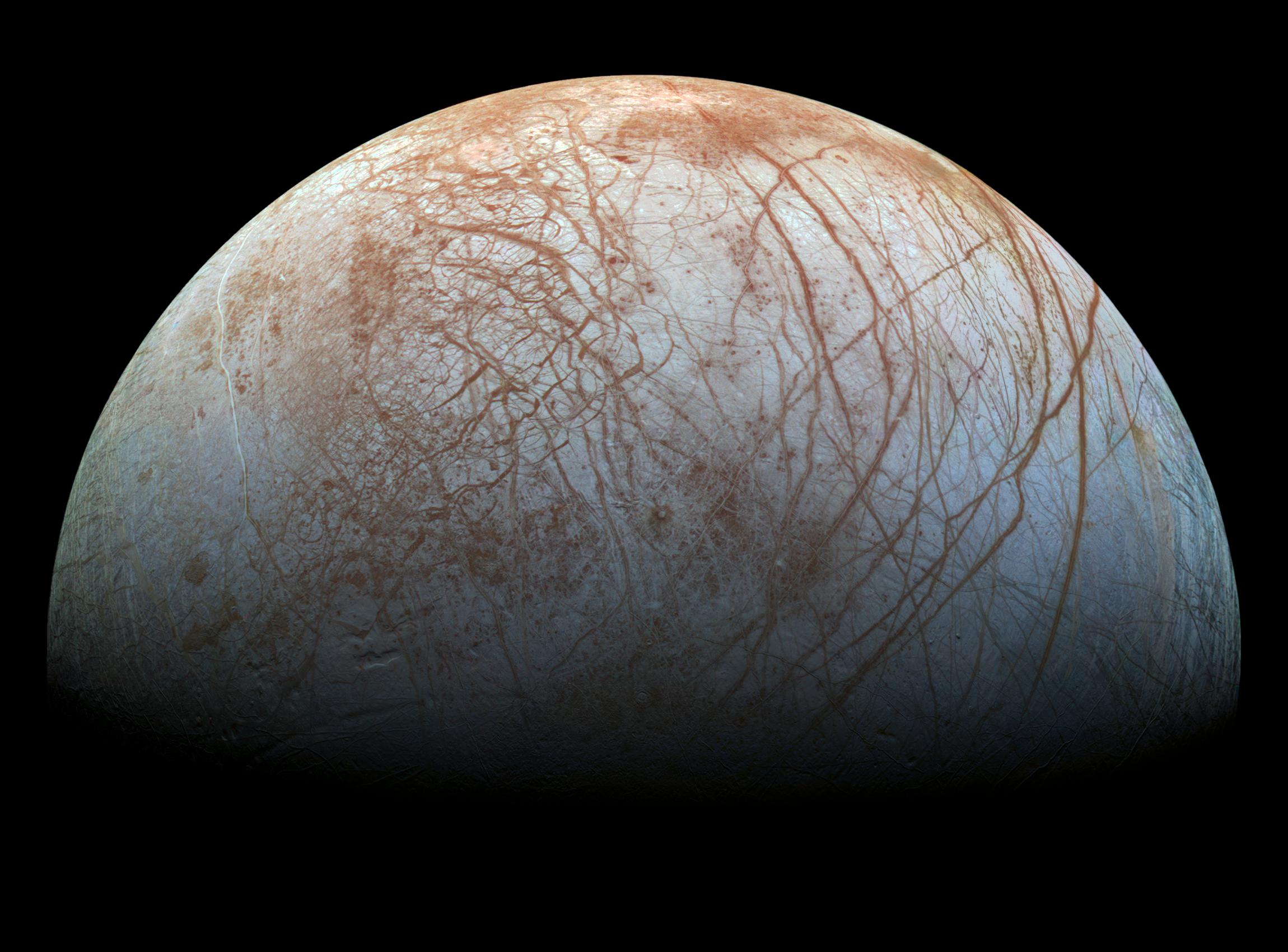

*Ariel as seen by Voyager 2, showing its extensive fault systems and canyons. Credit: NASA/JPL (Public Domain)*Introduction

Ariel, named after a spirit in Shakespeare's "The Tempest," was discovered by William Lassell in 1851. The moon gained attention when Voyager 2 images revealed its extensive fault systems and evidence of past geological activity, making it the most geologically interesting of Uranus's major moons.

Ariel's young surface and extensive faulting suggest it was once more active than it is today. Understanding Ariel is important for understanding the geological evolution of icy moons, the processes that can drive activity on small bodies, and the diversity of Uranus's moon system.

Physical Characteristics

Basic Properties

Ariel is a mid-sized icy moon:

- Radius: 579 km

- Mass: 1.35 × 10²¹ kg

- Density: 1.67 g/cm³ (low, indicating mostly ice)

- Surface gravity: 0.27 m/s² (very weak)

- Escape velocity: 0.56 km/s

Ariel's density suggests it's composed of roughly 55% water ice and 45% rock by mass.

Orbit

Ariel orbits in the middle of Uranus's major moons:

- Semi-major axis: 191,020 km

- Orbital period: 2.52 Earth days

- Rotation: Synchronous (same face always toward Uranus)

- Eccentricity: 0.0012 (nearly circular)

Extensive Fault Systems

Canyons and Faults

Ariel is crisscrossed by extensive fault systems that are among the most dramatic tectonic features in the outer solar system:

- Length: Some faults extend for hundreds of kilometers, creating canyon systems that rival Earth's Grand Canyon in scale

- Depth: Canyons reach depths of up to 10 km, cutting deep into Ariel's icy crust

- Type: Primarily graben structures—down-dropped blocks between parallel faults—indicating extensional tectonics

- Distribution: Cover much of the surface, creating a network of canyons and valleys

- Width: Canyons can be 10-50 km wide, creating vast chasms in the icy surface

The extensive faulting indicates significant crustal extension, suggesting Ariel's interior expanded at some point in its history. The fault systems are so extensive that they dominate Ariel's surface, making it one of the most tectonically modified moons in the solar system.

Formation Mechanisms

The faults likely formed from several possible processes:

Tidal heating: Past tidal heating from Uranus's gravity may have caused Ariel's interior to warm and expand, creating extensional stresses that fractured the surface. This would have occurred when Ariel was in a different orbital resonance, experiencing more tidal flexing than it does today.

Interior freezing and expansion: As Ariel's interior cooled, water ice may have expanded upon freezing (unusual, as ice typically contracts when freezing, but high-pressure ice phases can expand), creating extensional stresses.

Tectonic activity: Crustal extension from internal processes, possibly related to cryovolcanism or upwelling of warmer material from the interior.

Age: The faults formed in the past, possibly hundreds of millions of years ago, during a period of greater geological activity. The exact timing is uncertain, but the presence of craters on some fault surfaces suggests the faulting occurred early in Ariel's history.

The exact mechanism remains uncertain, and multiple processes may have contributed. Future missions to Uranus will help determine which mechanism was most important.

Surface Geology

Mixed Terrain

Ariel's surface shows a complex mix of terrain types that tells a story of geological activity and resurfacing:

- Heavily cratered terrain: Ancient, unchanged regions that preserve Ariel's early history, dating back 3-4 billion years. These regions are similar to Callisto's ancient surface, showing what Ariel looked like before geological activity began.

- Smooth plains: Young, resurfaced regions with very few craters, indicating recent geological activity. These smooth areas cover approximately 30-40% of Ariel's surface.

- Faulted regions: Areas with extensive faulting and canyon systems, showing evidence of tectonic activity. The fault systems often cut through both ancient and young terrain, providing clues about the timing of geological events.

- Bright appearance: Ariel has an albedo of 0.53, making it significantly brighter than its darker sibling Umbriel (albedo 0.19). This brightness suggests more exposed water ice on the surface.

The mix of terrain types suggests a complex geological history with multiple episodes of activity, resurfacing, and tectonic deformation. Unlike Umbriel, which appears to have been geologically dead for billions of years, Ariel shows clear evidence of past geological activity.

Resurfacing Processes

Some regions show extensive evidence of resurfacing, indicating Ariel was once more geologically active:

Smooth plains: Large areas with far fewer craters than expected for a surface of Ariel's age. The smooth plains appear to have been formed by material flowing over the surface, possibly from cryovolcanism or other processes.

Possible cryovolcanism: Material may have flowed over the surface, covering older craters and creating the smooth plains. The material could have been water ice, ammonia-water mixtures, or other volatile compounds that flowed like lava before freezing.

Age of resurfacing: The resurfacing occurred in the past, possibly 1-2 billion years ago, during a period when Ariel was more geologically active. The exact timing is uncertain, but the presence of some craters on resurfaced areas suggests the activity has largely ceased.

Extent: Resurfacing covers significant portions of Ariel's surface, particularly in the regions between the major fault systems. This suggests that resurfacing and faulting may have been related processes.

The resurfacing suggests Ariel was once more active, possibly driven by tidal heating from Uranus's gravity or internal heat from radioactive decay. The cessation of activity may have occurred when Ariel's orbit changed, reducing tidal heating, or when the internal heat source was exhausted.

Composition

Ice and Rock

Ariel's composition, inferred from its density of 1.67 g/cm³, suggests a mix of ice and rock:

- Water ice: Primary component, approximately 55% by mass. The ice is likely in the form of water ice (H₂O), possibly with small amounts of other ices like ammonia (NH₃) or methane (CH₄).

- Rock: Silicate material, approximately 45% by mass. The rocky component likely includes silicates, iron, and other minerals similar to those found in carbonaceous chondrite meteorites.

- Structure: Ariel may be differentiated, with an ice shell over a rocky core, similar to other mid-sized icy moons. However, the differentiation may be incomplete, with some mixing of ice and rock throughout the interior.

The density indicates significant rock content, more than would be expected for a pure ice body. This rock content suggests Ariel formed from material that included both ice and rock from the early solar system.

Surface Composition

Ariel's surface composition, studied through spectroscopy and imaging:

- Water ice: Primary component of the surface, exposed in many areas. The ice appears relatively pure, with less contamination than Umbriel's darker surface.

- Brighter material: Exposed ice in smooth plains and fault walls, creating Ariel's bright appearance. The exposure of fresh ice suggests recent geological activity that has brought subsurface ice to the surface.

- Albedo: 0.53 (reflects 53% of incident light), making Ariel significantly brighter than Umbriel's 0.19 albedo. This brightness is consistent with more exposed water ice and less dark material on the surface.

- Dark material: Some darker regions, possibly organic compounds or radiation-darkened ice, but less extensive than on Umbriel.

The brighter surface suggests more exposed ice, possibly from recent resurfacing or faulting that has exposed fresh material. The contrast with Umbriel's dark surface suggests different evolutionary paths for these two moons, despite their similar sizes and orbits.

Exploration History

Discovery

- 1851: Discovered by William Lassell

- 1986: Voyager 2 provided only close-up images

Voyager 2 (1986)

Voyager 2's brief encounter revealed:

- Extensive fault systems

- Evidence of past resurfacing

- Mixed terrain types

- Complex geology

Voyager 2's data is still being analyzed today.

Scientific Importance

Understanding Icy Moon Geology

Ariel provides crucial insights into the geological processes that shape icy moons:

- Tectonic activity: How extensional tectonics work on icy moons, creating fault systems and canyons. Ariel's extensive faulting demonstrates that even small moons can experience significant tectonic activity when conditions are right.

- Resurfacing: How surfaces are renewed through cryovolcanism or other processes. Ariel's smooth plains show that resurfacing can erase the geological record, making it difficult to determine a moon's complete history.

- Past activity: Evidence of past geological activity that has since ceased. Ariel demonstrates that moons can transition from active to inactive states, providing insights into the timescales of geological activity.

- Evolution: How moons evolve over time, from active worlds to geologically dead bodies. Understanding this evolution is crucial for understanding the diversity of moons in the solar system.

Comparison to Other Moons

Ariel demonstrates the diversity of geological processes and evolutionary paths among similar moons:

Diversity of activity: Despite being similar in size to Umbriel, Ariel shows evidence of past geological activity while Umbriel appears to have been inactive for billions of years. This demonstrates that size alone doesn't determine geological activity.

Different evolutionary paths: Ariel and Umbriel likely formed under similar conditions but have followed different evolutionary paths. Ariel's past activity may have been driven by different orbital resonances or internal heat sources.

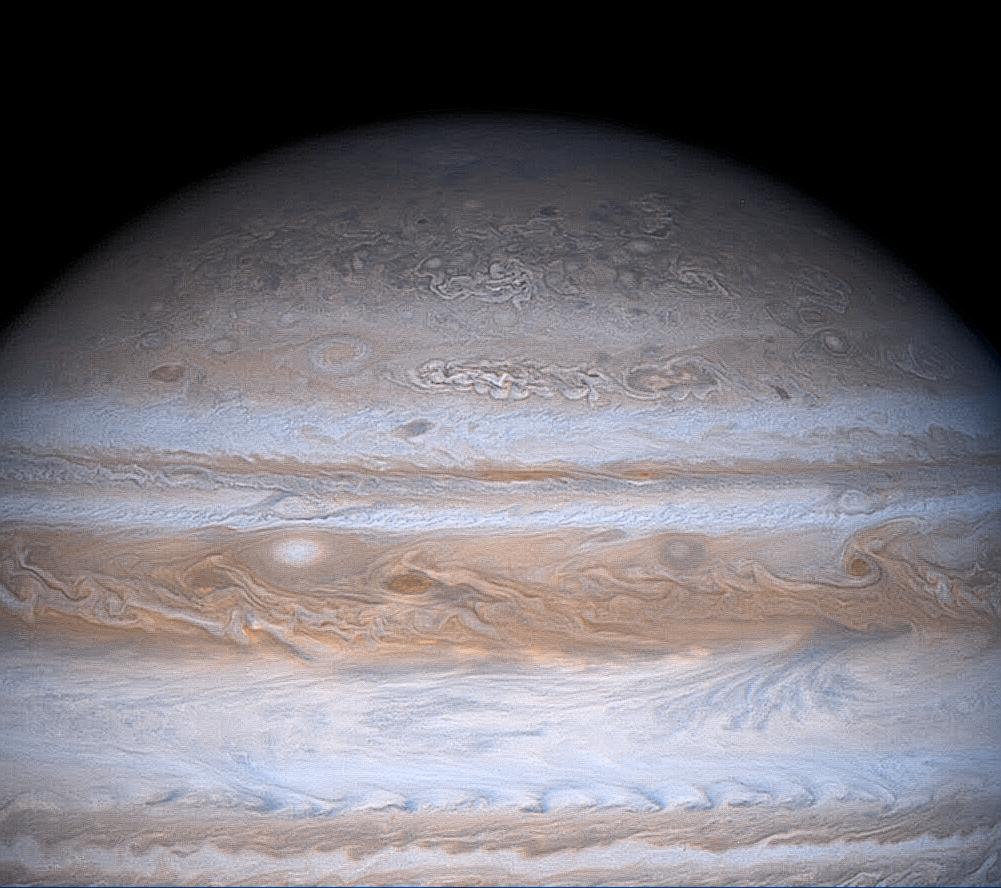

Different geological processes: Ariel's faulting and resurfacing show different processes than those seen on other moons. Comparing Ariel to Europa (with its linear features), Enceladus (with its geysers), and Ganymede (with its grooved terrain) reveals the diversity of geological processes possible on icy moons.

Tidal heating effects: Ariel's past activity, if driven by tidal heating, demonstrates how orbital resonances can drive geological activity even on small moons. The cessation of activity suggests that changes in orbital configuration can turn geological activity on and off.

Open Questions

Many mysteries remain about Ariel:

- Past activity: What drove the geological activity?

- Fault formation: How exactly did the faults form?

- Resurfacing: What caused the resurfacing?

- Current state: Is Ariel still active today?

- Formation: How did Ariel form?

- Future: How will Ariel evolve?

A dedicated mission to Uranus would help answer these questions.

Conclusion

Ariel is the most geologically interesting of Uranus's major moons, with extensive fault systems and evidence of past activity. Its young surface and complex geology make it a fascinating target for study, providing insights into the geological evolution of icy moons and the processes that can drive activity on small bodies. Understanding Ariel is essential for understanding the diversity of Uranus's moon system and the processes that shape icy worlds throughout the solar system.

For related topics:

- Umbriel - Ariel's darker sibling moon

- Miranda - Uranus moon with extreme topography

- Titania - Uranus's largest moon

- Uranus - The ice giant and Ariel's parent world

- Planetary Science & Space - Overview of planetary science topics

^[NASA Solar System Exploration - Ariel] NASA. (2024). Ariel: In Depth. NASA Solar System Exploration. https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/uranus-moons/ariel/in-depth/

^[Ariel Geology] Plescia, J. B. (1987). Cratering history of the Uranian satellites: Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon. Journal of Geophysical Research, 92(S02), 14918-14932.

^[Voyager 2 Ariel] Smith, B. A., et al. (1986). Voyager 2 in the Uranian system: Imaging science results. Science, 233(4759), 43-64.

^[Ariel Tectonics] Croft, S. K., & Soderblom, L. A. (1991). Geology of the Uranian satellites. In Uranus (pp. 561-628). University of Arizona Press.